“A crowd of people, workers, clerks and managers walk quickly at the streets

of Napoli, of Messene, of Syracuse and Tarant. Computers control the flow

of the economy and in the city harbours ocean liners and oil tankers of a

thousand tons moor, while from their airports many airplanes take off, with

hundreds of passengers.

The hasty visitor of our era cannot perhaps even think about that distant moment

in time when the coasts were still unpolluted, filled with rich forests; the

time when ships ready to fall apart would anchor after a long, tedious journey,

to unload groups of young soldiers who walked cautiously towards the deserted

beach, afraid that at any moment the dreadful outcry of the native soldiers attempting

to repel them would echo through the woods, depriving them once and for all of

the dream of a new country.

They carried a knife with them, from their old country and ashes from the holy

fire that had burned at the acropolis of their homeland, hoping that they would

be able to create new hearths, to build new homes where new, foreign wives would

live, taken by force or seduced with gifts and they would bear them children

with new, unspoiled blood in their veins.

Valerio Manfredi, The Western Greeks

|

|

| The Doric temple of Taranto dedicated

to Poseidon(?), one of the few preserved monuments of the ancient

city, famous for its wealth and size. The two columns are situated

on the islet that was the acropolis of the city. |

| |

The Myceneans had settled in the Apulian region at the end of the second

millennium B.C. As the region was inhabited by the natives Messapians and

Iapyges, there was only one colony created, Taranto, the sole colony of the

Lacedaemonians (henceforth: Spartans). The Spartans preferred to extend their

territory by conquering their neighbours rather than emigrating. At the time

when the Eyboeans and the Corinthians travelled to the West in search of

new places for settlement, the Spartans fought against their Messinian neighbours

for almost 20 years in order to occupy their land (First Messinian War, 743-724

B.C.). The city of Taranto was founded in 706 B.C. by the Spartan Phalanthus

and the Parthenians.

Taranto collided with the natives Messapians and, even

though the Tarantians (or Tarentines) lost their first battles, they prevailed

and offered many offerings to the Oracle of Delphi (First quarter of the

5th century B.C.)

|

|

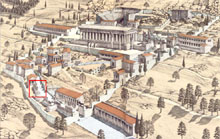

| Commemorating their victory over

the Messapians, the Tarantians, holding one tenth of their

loot, dedicated to Delphi, a monument of the sculptor Ageladas

that depicted captured women and horses. The monument dating

to the beginning of the 5th century (approximately 485 B.C.)

was in a prominent place, left of the Hiera Odos. Today, only

its base is preserved (red square). |

| |

Pausanias (10. 10.6-8) during his visit to Delphi in the 2

nd century

A.D. describes the historical course of the foundation of Taranto and the Tarantians’

monument of the Tarantians:

|

Reconstruction of Delphi and the location of the Tarantian

monument (red square)

© Delphi, Ekdotiki Athinon Publications |

The bronze horses and captive women dedicated by the Tarentines were made from

spoils taken from the Messapians, a non-Greek people bordering on the territory

of Tarentum, and are works of Ageladas the Argive. Tarentum is a colony of the

Lacedaemonians, and its founder was Phalanthus, a Spartan. On setting out to

found a colony, Phalanthus received an oracle from Delphi, declaring that when

he should feel rain under a cloudless sky (aethra), he would then win both a

territory and a city.

[7] At first, he neither examined the oracle himself nor informed one of his

interpreters, but came to Italy with his ships. But when, although he won victories

over the barbarians, he succeeded neither in taking a city nor in making himself

master of a territory, he called to mind the oracle, and thought that the god

had foretold an impossibility. For, never could rain fall from a clear and cloudless

sky. When he was in despair, his wife, who had accompanied him from home, among

other endearments placed her husband's head between her knees and began to pick

out the lice. And it chanced that the wife, such was her affection, wept as she

saw her husband's fortunes coming to nothing.

[8] As her tears fell in showers, and she wetted the head of Phalanthus, he realized

the meaning of the oracle, for his wife's name was Aethra. And so on that night

he took from the barbarians Tarentum, the largest and most prosperous city on

the coast. They say that Taras the hero was a son of Poseidon by a nymph of the

country, and that after this hero were named both the city and the river. For

the river, just like the city, is called Taras. [Translation by W.H.S. Jones,

Litt.D., and H.A. Ormerod, M.A.]

|

| Archytas |

The city of Taranto (Taras) was built on the cape that blocks the mouth

of the two lagoons. The city extended up to 570 hectares. At the end of

the 5

th century, democracy prevailed in Taranto which reached

its peak under the administration of the philosopher Archytas of Tarentum.

There were two famous statues of Hercules and Zeus at the city’s agora.

The statue of Zeus was the tallest statue of the Mediterranean world, reaching

a height of 18 meters. The wealth of the city had gradually led to the

decline of its power, and the Tarantians, who lived abundantly, would call

military troops from Sparta and Epirus to battle with their neighbors,

the Messapians and the Leukanians who were a constant threat.

During the conflicts with the Romans and the neighboring city of Thourioi, the

Tarantians called for the king of Epirus, Pyrros. He arrived, bringing some elephants

among other weapons, which terrorized the Romans who subsequently lost the first

battles; they soon regrouped and prevailed, while Pyrros, fled to Epirus. The

final destruction of the city took place in 209 B.C. when the Tarantians attempted

to recover the administration of their city with the alliance they made with

the Carthaginians. The Romans took over Taranto and looted the city, transporting

a large part of the loot to Rome, including the famous, tall statue of Hercules.

This statue was transported to Istanbul and during the occupation of the Francs

in 1204 it was melt in order to become coins.

In the centuries that followed, the city of Taranto was in decline; it also had

to survive pirate attacks, who forced the inhabitants of the city to withdraw

to the interior of the country. The revival of the city’s port started during

the short period of the French occupation at the beginning of the 19

th century.

|

| Mare Picollo and the islet of the acropolis

of ancient Taras. The bridge connects the city with the islet

and leads to the open bay of Taras (Mare Grande) |

| |

|

|

| Ancient Taras (picture © by Valerio M. Manfredi,

Greeks of the West). The dotted line shows the boundaries of the

city’s walls. |

The city of Taranto today. The Little Sea (Mare

Piccolo) proved to be an important incentive for the settlement of

the Spartans, since the bay of Taranto is generally harbourless.

The red circle defines the boundaries of the ancient city, buried

under the contemporary one. The blue arrow points out the position

of the Doric temple from which only two columns are preserved. |

| |

Strabo has an extensive description of the area of modern Apulia,

inhabited by the Messapians and by the Iapyges in the north, as well

as of the city

of Taranto. He also describes the founding of the city of Taranto by Phalanthus

and the Parthenians extensively; he uses the words of the historian Ephorus

who lived in the 4

th century B.C. but only a few excerpts of his

work are saved.

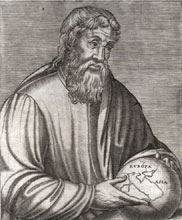

Strabo was born in a wealthy family from Amaseia

in Pontus. His mother was Georgian. He studied under various geographers

and philosophers; first in Nysa, later in Rome. He was philosophically

a Stoic and politically a proponent of Roman imperialism. Later he

made extensive travels to Egypt and Kush, among others. It is not known

when his Geography was written, though comments within the work itself

place the finished version within the reign of Emperor Tiberius. Some

place its first drafts around AD 7, others around 18.

Several different dates have been proposed for Strabo's death, but most

of them place it shortly after 23.

|

| The Greek geographer Strabo in

a 16th century engraving. |

|

Strabo,

Geography, 6.3. “Now that I have traversed the regions of Old

Italy as far as Metapontium, I must speak of those that border on them. And Iapygia

borders on them. The Greeks call it Messapia also, but the natives, dividing

it into two parts, call one part (that about the Iapygian Cape) the country of

the Salentini, and the other the country of the Calabri. Above these latter,

on the north, are the Peucetii and also those people who in the Greek language

are called Daunii, but the natives give the name Apulia to the whole country

that comes after that of the Calabri, though some of them, particularly the Peucetii,

are called Poedicli also. Messapia forms a sort of peninsula, since it is enclosed

by the isthmus that extends from Brentesium as far as Taras, three hundred and

ten stadia. And the voyage thither around the Iapygian Cape is, all told, about

four hundred stadia. The distance from Metapontium is about two hundred and twenty

stadia, and the voyage to it is towards the rising sun. But though the whole

Tarantine Gulf, generally speaking, is harborless, yet at the city there is a

very large and beautiful harbor, which is enclosed by a large bridge and is one

hundred stadia in circumference. In that part of the harbor which lies towards

the innermost recess, the harbor with the outer sea, forms an isthmus, and therefore

the city is situated on a peninsula; and since the neck of land is low-lying,

the ships are easily hauled overland from either side. The ground of the city,

too, is low-lying, but still it is slightly elevated where the acropolis is.

The old wall has a large circuit, but at the present time the greater part of

the city—the part that is near the isthmus—has been forsaken, but the part that

is near the mouth of the harbor, where the acropolis is, still endures and makes

up a city of noteworthy size. And it has a very beautiful gymnasium, and also

a spacious market-place, in which is situated the bronze colossus of Zeus, the

largest in the world except the one that belongs to the Rhodians. Between the

marketplace and the mouth of the harbor is the acropolis, which has but few remnants

of the dedicated objects that, in early times, adorned it, for most of them were

either destroyed by the Carthaginians, when they took the city, or carried off

as booty by the Romans, when they took the place by storm. Among this booty is

the Heracles in the Capitol, a colossal bronze statue, the work of Lysippus,

dedicated by Maximus Fabius, who captured the city.

|

| Coin (stater) of Taranto, 4th century B.C. The mythical

colonist Taras is depicted on a dolphin. According to the myth, Taras

was the son of Poseidon and of a local nymph, Satyria. |

In speaking of the founding of Taras, Antiochus says: After the Messenian war

broke out, those of the Lacedaemonians, who did not take part in the expedition,

were adjudged slaves and were named Helots, and all children who were born in

the time of the expedition, were called Partheniae and judicially deprived of

the rights of citizenship, but they would not tolerate this, and since they were

numerous, formed a plot against the free citizens; and when the latter learned

of the plot they sent secretly certain men who, through a pretence of friendship,

were to report what manner of plot it was; among these was Phalanthus, who was

reputed to be their champion, but he was not pleased, in general, with those

who had been named to take part in the council. It was agreed, however, that

the attack should be made at the Hyacinthian festival in the Amyclaeum when the

games were being celebrated, at the moment when Phalanthus should put on his

leather cap (the free citizens were recognizable by their hair); but when Phalanthus

and his men had secretly reported the agreement, and when the games were in progress,

the herald came forward and forbade Phalanthus to put on a leather cap; and when

the plotters perceived that the plot had been revealed, some of them began to

run away and others to beg for mercy; but they were bidden to be of good cheer

and were given over to custody; Phalanthus, however, was sent to the temple of

the god to consult with reference to founding a colony; and the god responded, "I

give to thee Satyrium

|

|

|

| The walls of the city of Mandyrion (Manduria).

Mandyrion was the eastern boundary of the Tarantian prevalence. The city

was protected by a triple row of walls. Under these walls, the king of

Sparta Archidamus was killed; he had come to the city from Sparta in 338

B.C. when the Tarantians requested his help. |

| |

(8) Satyrium was the cape of Italy, where contemporary Puglia (Apulia) is found.

For the march of Archidamus in Southern Italy, Diodorus Siculus states

(XVI, 63):

[..] At the same period,

9

the Tarantians were at war with the Leukanians and had sent their ancestors,

the Lacedaemonians, as ambassadors, seeking for military aid. The Spartans were

more than willing to assist, due to their kinship and have brought together in

a haste their navy and infantry and as their ruler they placed their own king,

Archidamus. As they were about to embark on Italy, the Lyctians

10 pleaded with

them, to go to their aid first. The Lacedaemonians were convinced and parted

for Crete, where they defeated the

mercenaries and restored the Lyctians to their own land again… Subsequently,

Archidamus set sail for Italy, where he joined forces with the Tarantians, but,

alas, died in a battle, after a brave fight

11. He was a

man of great praise for his strategic qualities and for his life in general,

who had only been dispraised for being in league with the Phoceans, as the one

begetting the capture of Delphi. Archidamus was king of Lacedaemonians for twenty

- three years.

(9) In 338 B.C., the battle of Chaironeia took also place; the Macedonians

of Philip and of Alexander the Great prevailed over the coalition of the

Greeks of Southern Greece.

(10) Lyctos: city of Crete conquered by the Phocaean Phalaikos.

(11) Plutarch in the Life of the Spartan king Agis, who succeeded Archidamus

(360-338 B.C.), mentions that the death of Archidamus occurred at the city of

Mandyrion.

The ancient city of Taranto has been covered up by the modern city, but the excavations

in the city and the surrounding area, have brought to light unique findings which

clearly reflect the cultural and social standards of the city. The art in the

Apulian region has surpassed even the Greek standards, creating unique impressive

forms, with pioneering artistic creations. These findings are exhibited at the

Museum of the city of Taranto.

|

|

| Artifacts from the city of Taranto

and the Apulian region, exhibited at the Museum of Taranto. |

| |

Taranto was unable to extend to the east since the Messapians blocked their

prevalence. The city in an effort to preserve its interests, built a fortification

wall around the Gallipoli peninsula, at the entrance of the bay of Taranto.

The city, according to Pliny belonged to the Messapians and was called

Anxa. After its occupation by the Tarantians in 265 B.C., it was conquered

by the Romans, while in the centuries that followed in the Christian era,

the city shared the same fate with the rest of Apulia.

|

|

| The peninsula of Gallipoli at the entrance

of the bay of Taras (Taranto) was a colony of the Tarantians

in an effort to maintain control of the bay area. |

At the entrance of the peninsula, there

is an impressive fountain of the Hellenistic period. |

| |