The

Old Town of Corfu, on the Island of Corfu off the

western coasts of Albania and Greece, is located in a strategic position

at the entrance of the Adriatic Sea, and has its roots in the 8th century

BC. The three forts of the town, designed by renowned Venetian engineers,

were used for four centuries to defend the maritime trading interests of

the Republic of Venice against the Ottoman Empire. In the course of time,

the forts were repaired and partly rebuilt several times, more recently

under the British rule in the 19th century. The mainly neo-classical housing

stock of the Old Town is partly from the Venetian period, partly of later

construction, notably the 19th century. As a fortified Mediterranean port,

Corfu's urban and port ensemble is notable for its high level of integrity

and authenticity.

Description

The island of Corfu (in Greek: Kerkyra) lies in the Adriatic

Sea off the western coast of Greece and Albania. The Old Town of Corfu

lies between two fortresses midway along the island’s eastern coastline.

The Old Citadel and the New Fort form two remarkable monuments in the

urban fabric. To the east, the canal dug by the Venetians has transformed

the rocky promontory on which the Old Citadel was founded into an island

looking down over the tiny harbour of Mandraki. The citadel retains the

imposing Venetian fortifications, restructured by the British, laid out

on three levels on the far side of the canal linked by a footbridge to

the Spianada. A first outer wall leads to the frontal fortification,

consisting of two orillon bastions (Martinengo and Savorgnan) and a curtain

through which the main gate enters (around 1550). A stone bridge crosses

a broad ditch along which runs a 19 th century barracks. A second wall

protects the base of the two fortified peaks, and access to it is via

a series of ramps and stairs. A vaulted passage leads to the harbour

of Mandraki which itself also retains a monumental gate, now closed.

Some buildings on various levels, mainly dating from the 19 th century,

have been preserved. These include the former Venetian prisons, raised

in height by the British, four powder magazines, the hospital, which

stretches from one peak to the other, two barracks, and the Church of

St. George in the form of a Doric temple (1840).

The imposing structure of the New Fort dominates the north-western sector

of the Old Town. A pentagonal salient, a half-salient, and the small

fort of Punta Perpetua are connected by a rampart and command the old

harbour.

Long sloping tunnels lead to the British barracks and the two bastions

of the Seven Winds linked by a curtain wall and looking out over the

countryside. These look down on 164.a broad ditch and two bastions preserved

from the second Venetian perimeter wall. The two gates of the New Fort

still exist, as does the church of Panagia Spiliotissa (rebuilt in 1739).

The ring road around the Old Town follows the line of the ancient town

wall, some traces of which remain to the west and south and one gate,

the Spilia Gate, of the original four (Royal Gate, St Nicholas Gate,

Raimonda Gate).

The outlines of the Old Town were determined by lack of space and the

needs of defence. The urban fabric forms a compact core consisting of

ten quarters, differentiated by their form. The quarters which range

over the three low hills (Campielo, Agion Pateron, and Agiou Athanassiou)

are irregular and fragmentary in their make-up, a sure sign of the original

suburbs preserved from the demolition necessary for the construction

of the perimeter wall. They are characterised by a network of radial

streets, small squares, and compact blocks of housing clustered around

the churches. The outskirts of these areas, in transition, and the quarters

built in continuation of the perimeter wall present a more regular framework,

especially those which open out behind the Spianada in a grid of straight

lines running east-west.

The two main streets running east-west and the north-south axis which

once connected the Old Citadel to the four gates of the perimeter wall

follow an ancient outline. This simple traffic system, dictated by strategic

imperatives, contrasts with the secondary alleys (the kantounia,

between 1m and 3m wide) which form a complex network of stairs and vaulted

tunnels running through a series of small squares, of which Kremasti

Square is a typical example.

The restricted space within the perimeter dictated the construction

of multi-storey dwellings ranged indiscriminately in serried ranks along

the streets. Though the Old Town must have numbered many a patrician

dwelling during the Venetian period, only a few of these can be identified

in the present day, such as the houses of the Ricchi and Yallina families

(17 th century). The house fronts of this period are characterised by

regular rows of windows, stone balconies, ground-floor arcades, and a

red and ochre rendering that contrasts with the stone door and window

jambs. Many feature doorways ornamented with sculptures. Some public

buildings from the Venetian period still survive: the door of one of

the grain stores (1592), the pawnbroker’s (1630) that forms part of the

Commissioners’ Palace, part of the Spilia barracks, and the Grimani barracks

to the south of the Spianada.

The trend towards building upwards was accentuated in the 19 th century

when the old buildings were raised to anything up to six storeys or,

in most cases, replaced by new buildings which often occupied more space

than in the past by annexing the courtyards. The wider frontages were

divided into three vertical sections, always with many windows, but tended

to become more uniform, particularly along sections of the main streets,

while remaining sober in their classically inspired ornamentation. Balconies

on every floor created a sense of movement and variety in the facades.

Spianada, the esplanade which divides the town from the Old Citadel,

takes up one-third of the surface area of the Old Town. Once the most

populous of the suburbs in the 16 th century, it attained its present

size in the 17 th century for military reasons and is still bordered

by 18 th century barracks. In the late 18 th and early 19 th centuries

it became an architectural showcase dedicated to leisure activities and

civil functions. The French embellished it by constructing arcade-fronted

buildings, the Liston, to the west and planting trees. Under the British

it became a monumental open space with the Neo-Classical Palace of St

Michael and St George (1819-23), once the residence of the Commissioners,

to the north and to the south the circular Ionic temple dedicated to

Maitland: both are the work of George Whitmore (1775-1862).

At the centre of the Old Town stand two large squares, each leading

off one of the two main streets. On Dimarchion Square, once the social

and cultural centre of the Venetian town, which lies on the slopes of

the hill of Agiou Athanassiou, stand the 18 th century Cathedral of St

James, the former residence of the Latin Archbishop (rebuilt in 1754),

and the Loggia Nobilei (1663-69), converted into a theatre in

1720 and home of the Town Hall since the early 20 th century.

On Heroon Square stand the churches of St John (pre-16 th century) and Phaneromeni,

a basilica with three aisles dating from the early 18 th century and

altered in 1832 by Corfiot architect Ioannis Chronis, who designed many

public buildings in the Neo-Classical style for the Old Town, including

the Ionian Bank which stands on the same square, the home of Ioannis

Kapodistrias, the first Greek governor, and the Ionian Parliament (1854,

then restored after the bombings in 1943). To the north of this square

stands the Church of St Spyridon (1589-94, altered in 1670), which houses

the relics of the patron saint of the town and the island. Although the

Orthodox faith was upheld during the centuries of foreign occupation,

contact with the Latin West also influenced the religious architecture

of the Old Town, which shows a strong Byzantine tradition. The example

of the single-aisled church, often with a low exterior narthex running

around the exterior, is much more common than the three-aisled basilica,

although both reflect the repertoires of the Renaissance and the Baroque

style. The simplicity of the facades offers a remarkable contrast to

the elaborate interior decoration. Many ancient churches were enlarged

and renovated in the 18 th century.

History and development

Corfu, the first of the Ionian Islands encountered at the entrance to

the Adriatic, was annexed to Greece by a group of Eretrians (775-750

BCE). In 734 BCE the Corinthians founded a colony known as Kerkyra to

the south of where the Old Town now stands. The town became a trading

post on the way to Sicily and founded further colonies in Illyria and

Epirus. The coast of Epirus and Corfu itself came under the sway of the

Roman Republic (229 BCE) and served as the jumping-off point for Rome’s

expansion into the east. In the reign of Caligula two disciples of the

Apostle Paul, St Jason, Bishop of Iconium, and Sosipater, Bishop of Tarsus,

introduced Christianity to the island. Corfu fell to the lot of the Eastern

Empire at the time of the division in 336 and entered a long period of

unsettled fortunes, beginning with the invasion of the Goths (551).

165.The population gradually abandoned the old town and moved to the

peninsula surmounted by two peaks (the korifi) where the ancient

citadel now stands. The Venetians, who were beginning to play a more

decisive role in the southern Adriatic, came to the aid of a failing

Byzantium, thereby conveniently defending their own trade with Constantinople

against the Norman prince Robert Guiscard. Corfu was taken by the Normans

in 1081 and returned to the Byzantine Empire in 1084.

Following the Fourth Crusade and the sack of Constantinople by the Crusaders

in 1204, the Byzantine Empire was broken up and, in return for their

military support, the Venetians obtained all the naval bases they needed

to control the Aegean and the Ionian Seas, including Corfu, which they

occupied briefly from 1204 to 1214. For the next half-century, the island

fell under the sway of the Despots of Epirus (1214-67) and then that

of the Angevins of Naples (1267-1368), who used it to further their policies

against both the Byzantine Empire now re-established in Constantinople

and the Republic of Venice.

The tiny medieval town grew up between the two fortified peaks, the

Byzantine Castel da Mare and the Angevin Castel di Terra,

in the shelter of a defensive wall fortified with towers. Writings from

the first half of the 13 th century tell of a separation of administrative

and religious powers between the inhabitants of the citadel and those

of the outlying parts of the town occupying what is now the Spianada.

In order to assert its naval and commercial power in the Southern Adriatic,

the Republic of Venice took advantage of the internal conflicts raging

in the Kingdom of Naples to take control of Corfu (1386-1797). Alongside

Negropont (Chalcis), Crete, and Modon (Methoni), it would form one of

the bases from which to counter the Ottoman maritime offensive and serve

as a revictualling station for ships en route to Romania and the Black

Sea.

The ongoing work on defining, improving, and expanding the medieval

fortified perimeter reflects the economic and strategic role of Corfu

during the four centuries of Venetian occupation. In the early 15 th

century activity concentrated on the medieval town, with the development

of harbour facilities (docks, quays and arsenals) and continued with

the renovation of the defence works. Earlyin the following century a

canal was dug, cutting off the medieval town from its suburbs. Following

the siege of the town by the Turks in 1537 and the burning of the suburbs,

a new programme of works was launched to isolate the citadel further

and strengthen its defences. The strip of land (now the Spianada) cleared

in 1516 was widened by demolishing houses facing the citadel walls, two

new bastions were raised on the banks of the canal, the elevation of

the perimeter walls was lowered, and the two castelli were replaced

by new structures. The work, based on plans drawn by Veronese architect

Michele Sanmicheli (1487-1559), were completed in 1558, bringing the

town’s defences up to date with the rapid progress made in artillery

in recent decades.

Yet another siege by the Turks in 1571 decided theVenetians to embark

on a vast project covering themedieval town, its suburbs, the harbour,

and all themilitary buildings (1576-88). Ferrante Vitelli, architect

to the Duke of Savoy, sited a fort (the New Fort) on the low hill of

St Mark to the west of the old town to command the surrounding land and

at sea, and also the 24 suburbs enclosed by a ditched wall with bastions

and four gates.

More buildings, both military and civil, were erected and the 15th century

Mandraki harbour was restructured and enlarged. At the same time, the

medieval town was converted to more specifically military uses (the cathedral

was transferred to the new town in the 17 th century) to become the Old

Citadel.

Between 1669 and 1682 the system of defences was further strengthened

to the west by a second wall, the work of military engineer Filippo Vernada.

In 1714 the Turks sought to reconquer Morea (the Peloponnese) but Venetian

resistance hardened when the Turkish forces headed towards Corfu. The

support of Christian naval fleets and an Austrian victory in Hungary

in 1716 helped to save the town. The commander of the Venetian forces

on Corfu, Giovanni Maria von Schulenburg, was inspired by the designs

of Filippo Vernada to put the final touches to this great fortified ensemble.

The outer western defences were reinforced by a complex system of outworks

on the heights of two mountains, Abraham and Salvatore, and on the intermediate

fort of San Rocco (1717-30).

The treaty of Campo Formio (1797) marked the end of the Republic of

Venice and saw Corfu come under French control (1797-99) until France

withdrew before the Russian-Turkish alliance that founded the State of

the Ionian Islands, of which Corfu would become the capital (1799-1807).

The redrawing of territorial boundaries in Europe after the fall of Napoleon

made Corfu, after a brief interlude of renewed French control (1807-14),

a British protectorate for the next half-century (1814-64).

As the capital of the United States of the Ionian Islands, Corfu lost

its strategic importance. Under the governance of the British High Commissioner

Sir Thomas Maitland (1816-24), development activity concentrated on the

Spianada; his successor, Sir Frederic Adam (1824-32), turned his attention

towards public works (building an aqueduct, restructuring the Old Citadel

and adding new military buildings at the expense of the Venetian buildings,

reconstruction and raising of the town’s dwellings) and the reorganisation

of the educational system (the new Ionian Academy was opened in 1824),

contributing to the upsurge in intellectual interests sparked during

the French occupation. At the same time, the British began demolishing

the outer fortifications on the western edge of the town and planning

residential areas outside the defensive walls.

In 1864 the island was attached to the Kingdom of the Hellenes. The

fortresses were disarmed and several sections of the perimeter wall and

the defences weregradually demolished. The island became a favoured holiday

destination for the aristocracy of Europe. The Old Town was badly damaged

by bombing in 1943. Added to the loss of life was the destruction of

many houses and public buildings (the Ionian Parliament, the theatre,

and the library), fourteen churches, and a number of buildings in the

Old Citadel. In recent decades the gradual growth of the new town has

accelerated with the expansion of tourism.

OUTSTANDING UNIVERSAL VALUE, INTEGRITY AND AUTHENTICITY

Integrity and Authenticity

Integrity

The Old Town of Corfu is a fortified Mediterranean harbour retaining

traces of Venetian occupation, including the Old Citadel and the New

Fort, but primarily of the British period.

The strict legal measures enacted after World War II, and the listing

of the town for protection as a cultural monument in 1967 have provided

the basis for the control of changes and the possibility to retain the

integrity of the town. During the British period, three forts were preserved:

the Old Fortress, the New Fortress and the small island of Vidos. The

plan provided for the demolition of all the western forts. The British

did demolish the south-west side in 1937 and fort of Sotiros in 1938

to give space for prisons. In the old and new fortresses, the British

intervention related to internal restructuring and some new additions.

The overall form of the fortifications has been retained. Nevertheless,

like most fortifications, Corfu has faced many severe military attacks,

causing destruction, demolition and rebuilding. The interventions of

the 19 th century and the rebuilding after the World War II have in fact

reduced the historic fabric of the property. Only a relatively small

part of the structures actually dates from the Venetian period.

Authenticity

Corfu developed from a small Byzantine town along the lines of a western

urban model, which can be seen on all cultural levels and displayed in

the town’s structure and form. The Old Town of Corfu today occupies the

same area as the ancient town whose overall design it still reflects,

with the two fortifications, the open space of the Spianada, the compact

urban core with its different quarters and the streets. This urban fabric

has been shaped by centuries of demolition and reconstruction dictated

by military needs. In the 19 th century the British were the first to

begin dismantling the complex Venetian defence system, the scale of which

is amply illustrated by the many maps still extant. The British example

was followed by the Greek government after 1864.

About 70% of the pre-20 th century buildings date from the British period.

There were no large openings made in Corfu as was the case in many other

fortifications. Some of the dwellings have undergone further modifications

in the 20 th century, such as the addition of an extra floor.

World War II bombing destroyed some houses and buildings in the Old

Town, particularly in the western section, where whole blocks were destroyed.

The buildings thus lost were in part replaced by new constructions in

the 1960s and 1970s.

These interventions represent a particular juncture in history and express

the aesthetic attitudes of their time, clearly distinguished from previous

buildings. The existence of rich records on the old form of the town

has ensured full documentation in the case of interventions to existing

buildings. The fortifications of Corfu and the historic urban areas have

been subject to various armed conflicts and consequent destruction. The

present form of the ensemble results from the works in the 19 th and

20 th centuries, even though based on the overall design of previous

phases, particularly in the Venetian period. ICOMOS considers that the

fortified ensemble of Corfu is authentic, despite the many structural

alterations resulting from its major strategic importance as a military

position. It has been actively involved in many conflicts which took

place at the point of contact between the West and the Mediterranean

East from the 15 th to the 20 th centuries. It has been rebuilt several

times, and altered to allow for developments in weapons of attack and

principles of defence, successively by the Venetians and by the British.

The integrity of the fortified ensemble, in its current state of conservation,

is satisfactory in terms of expressing its outstanding value. ICOMOS

considers that the urban site of Corfu is representative of an urban

history which is closely associated with the structure of forts and ramparts.

ICOMOS considers however that the authenticity and integrity of the urban

fabric are primarily those of a neo-classical town.

In conclusion, ICOMOS considers that the authenticity and integrity

of the fortified ensemble of Corfu enable the expression of its outstanding

value.

Comparative analysis

The comparative analysis in the 2006 nomination document refers to the

following Mediterranean fortified cities: Rhodes, Valletta, Dubrovnik,

Trogir, and Heraklion.

In the supplementary information provided by the State Party, the comparison

has been extended to several other port towns in Italy, the Near East

and the Dalmatian coast.

Corfu is distinguished partly due to archaeological evidence of history

from the 8 th century BC and from the Byzantine period.

It is argued by the State Party that Corfu is characterised due to its

European influences and for its identity resulting from its role as a

crossroads of civilisations. The fortifications of the Venetian period,

designed by architects Sanmicheli, gave Corfu a major role as one of

the strategic military bases of Venice at the entrance to the Adriatic

Sea. It is also one of the few areas that avoided Ottoman occupation

keeping its western character.

There are a number of important fortifications in the eastern Mediterranean

region. Of these, Valletta and Dubrovnik are certainly the most impressive.

The maritime republic of Venice established its reign through a series

of fortifications along the Dalmatian coast, and Corfu was one of these.

The Ottoman Empire ruled in the inland of the Balkans and in the eastern

part of the Mediterranean, including the old town of Rhodes and the town

of Heraklion on the island of Crete. From the mid 14 th century Dubrovnik

became an autonomous republic and a rival to Venice. Valletta instead

was ruled by the Knights of Malta and remained the most important fortified

port in this part of the Mediterranean until the 20 th century.

ICOMOS considers that Corfu certainly had an important strategic position

at the entrance to the Adriatic Sea. For this reason it also had to face

the many attacks by the Ottomans. Historically, the property has its

origins in antiquity, but architecturally the fortification represents

a typical Renaissance fort, which was rebuilt several times.

The housing stock is in neo-classical style, but without special architectural

features for which it could be distinguished.

ICOMOS considers that the comparative study that accompanies the new

dossier is satisfactory, and that it enables a suitable assessment of

the value of the property.

Justification of the Outstanding Universal Value

The State Party considers that Corfu has an Outstanding Universal Value

for the following:

The Old Town of Corfu, internationally renowned, is a unique cultural

entity of a high aesthetic value: the aesthetic value is recognised in

the structure and form of the once-walled town, as well as in its arts,

letters and social life. The Old Town developed diachronically, through

the osmosis of features of the two worlds of the Mediterranean, the East

and the West. It has been preserved, alive and substantially unaltered,

until the present day.

The defence system and the urban fabric were designed and developed

during the Venetian period, from the 15 th to the 18 th centuries, and

then by the British Empire during the 19 th century.

The importance of Corfu’s fortifications for the history of defensive

architecture is huge. From both the technical and aesthetic point of

view they constitute one of the most glorious examples preserved, not

only in Greece, but across the Eastern Mediterranean more widely. At

various occasions, Corfu had to defend the Venetian maritime empire against

the Ottoman army.

Neo-classical in its architecture, the old town bears witness to the

duration of European architectural and cultural influence in the Balkans,

which were mainly dominated by the Ottoman empire. Corfu is also important

for studying the development of urban multi-storey buildings, since it

is the first Greek city in which the idea of horizontal ownership appeared.

The composite character of the town that resulted from its history and

the ability to assimilate differences without conflict led to the development

of a particular cosmopolitan atmosphere with intense European symbolism.

http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/978

|

|

| The Francs created Liston, reminiscent of Rue Rivoli in Paris |

The Palace of Michail and Georgiou, house of the English Commissioner, bearing neoclassical elements. |

| |

|

|

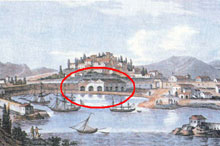

| In the Gulf of Gouvia, 9 kilometres north of the city of Corfu, the Venetians had built their dockyards (in red circle). |

The dockyards as they are today. |

| |